Over half a century later, rumors still swirl around Dawson Forest and the mysterious remnants of Dawson County’s past in the Cold War.

Though the Georgia Nuclear Aircraft Facility has been out of commission for nearly 50 years, local residents can still be heard whispering about two-headed deer and oak leaves the size of elephant ears spotted around the nuclear facility’s remains.

For nuclear engineer and author, Dr. James Mahaffey, the task of unraveling the history behind Dawson County’s top-secret nuclear test site and separating facts from the fiction has led to decades of research and hard work.

“Everything we knew started out as a rumor, and some of them were right and some of them were wrong,” Mahaffey said. “Not so much anymore but back then everything nuclear was, by its nature, a secret.”

Since his graduate studies at Georgia Tech in the 1970s, Mahaffey has compiled research on the Georgia Nuclear Aircraft Laboratory (GNAL) which has been published in his 2017 book Atomic Adventures where he discusses what happened behind closed doors at the site.

“It just gradually shaped into this fantastic facility. It was a singular facility. It wasn’t like anything else in the world, and it was in Dawsonville,” Mahaffey said. “It was out in the woods. That’s what they wanted. They wanted it where nobody would sneak around and want to know what it was, but that didn’t work.”

Rumors immediately began circulating when locals caught wind of a secretive laboratory being built inside the forest.

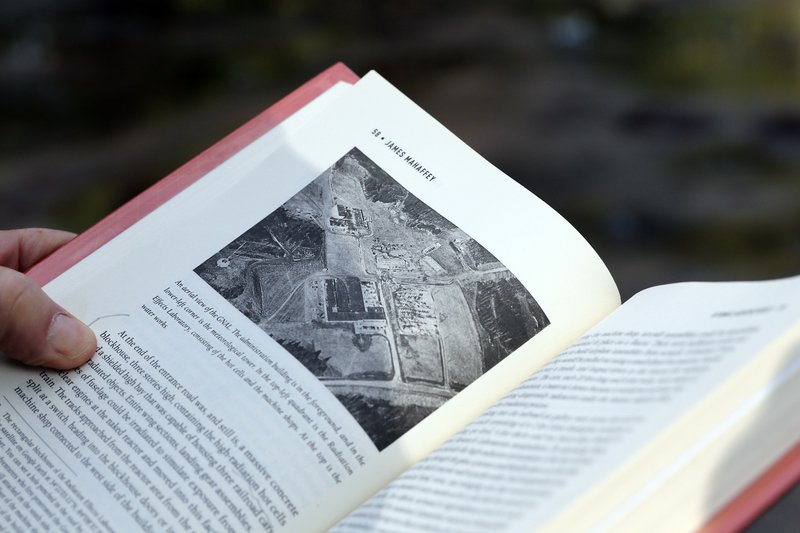

In the late 1950s, the United States Air Force purchased property in Dawson Forest to build the GNAL which was then operated by Lockheed Martin. The site needed to be developed in order for it to house the nuclear reactors, firehouse, administration building and the radiation effects facility which meant clear cutting thousands of trees, Mahaffey said.

“You couldn’t be on the property unless you had a security clearance and logging truck drivers didn’t have security clearances,” Mahaffey said. “What they did was they just piled up all these dead trees, thousands of dead trees in the exact center of the thing and set fire to it.”

When Mahaffey conducted interviews for his research, he recalls firsthand witnesses reporting red and orange glowing skies that spread over Dawsonville.

“The yellow glow from this huge bonfire reflected off the clouds and people in the area within miles of the place would see that and they were thinking this very secretive atomic place, this is the end of the world,” Mahaffey said.

Theories ran wild and unrestrained during the lab’s tenure in the county. Mahaffey said a popular rumor that circulated was that the facility was built to study flying saucers that had fallen in New Mexico and were brought to Georgia.

“The Air Force didn’t do enough to squash such rumors because that was completely off and that didn’t give it away,” Mahaffey said.

What was actually happening inside the lab was a series of tests on components for the nuclear-powered aircraft that the Air Force wanted.

Since World War II and the discovery of nuclear energy through atomic weapons, scientists began experimenting with this new power source to see if there could be a use beyond destroying cities, Mahaffey said. The Air Force concerned itself with protecting its pilots and looking at creating an aircraft powered by nuclear energy.

“If you could cause fission in that uranium it makes a great deal of power in a very small space,” Mahaffey said. “I mean you could have a thing that’s the size of basketball that gives you a billion watts of power.”

On paper, it seemed feasible as an incredible amount of power could be housed in a very small space, however the findings from the Dawsonville laboratory proved that nuclear aircraft would take more than what was originally thought.

“Any nuclear reactor on this earth has shielding,” Mahaffey explained. “It’s got lead, concrete, steel, you know, heavy things to keep it from killing everybody, but you put it in an airplane and you can’t have concrete and steel and lead. It’s got to be naked.”

Components for nuclear-powered engines were assembled in a facility in Idaho then brought to Dawsonville for testing inside the reactor. In Mahaffey’s research, he discovered that the facility found that rubber tires either melted or turned to rock when exposed to different radiation. Hydraulic fluids turned into a tacky substance akin to chewing gum. Transistors in the radio system were immediately killed by radiation.

The other aspect of the Dawsonville facility was testing the effects of radiation on the environment and living creatures.

“What does flying over a farm with a nuclear aircraft do to the farm? Well, it kills everything on the ground. It kills trees, grass, crops, insects, birds, anything. It might even kill the farmer if he’s out looking at it so what are you going to do about that? And also, what happens when one of these things crashes,” Mahaffey said. “If a jet plane crashes you clean it up and you pay the people for the house that it destroyed and all that, but what if it’s a nuclear aircraft? Nuclear aircraft - when it crashes - it makes a five mile radius area contaminated with long lasting radionuclides and you have to fence it off so nobody can go there. Are you really willing to have that as part of your Air Force operations?”

The effects of radiation were tested through controlled experimentation but also through observation of what Mahaffey describes as “instant taxidermy” of animals caught inside the kill zone around the outside of the operational reactor.

“Any animal like a toad frog that happened to be hopping around on the ground when the reactor was turned on, he died and interestingly it also killed all the bacteria in and around the frog,” Mahaffey said.

“When those [bacteria] die, it doesn’t deteriorate so you have this dead frog that you can put on your mantle and it’ll just stay there.”

According to Mahaffey, the scientists conducted many experiments with animals including releasing rats and studying the effects of radiation on them.

“I heard a rumor that the largest animal they ever irradiated was a mule and the mule died of course, and like a toad frog it would not deteriorate in a normal way,” Mahaffey said.

Billions of dollars were poured into the Nuclear Aircraft Project that GNAL was part of during the 1960s, but funding was cut in the John F. Kennedy administration. The GNAL was closed in pieces and shut its completely in 1971.

The GNAL buildings inside Dawson Forest were dismantled and hauled away. The hot cell building, the only remaining structure still standing, was boarded up with stainless steel to keep intruders from entering the radioactive building. To this day, the building remains radioactive with particulates of Cobalt 60.

According to Mahaffey, traces of Cobalt 60 radiation are still present around the building, but it’s not something people should be afraid of in 2020.

“You can still detect it if you have sensitive equipment but is it dangerous? Probably not. I mean, you’d have to eat the dirt to get it into your system,” Mahaffey said.

What makes Dawsonville’s secret nuclear facility stand out from other nuclear facilities for Mahaffey is the very detailed extent to which they dug into the dangers of nuclear fission products.

“An enormous amount of work was done to find out how having this reactor affects the environment. I’ll give them that,” Mahaffey said. “They wanted to find out how groundwater would transport radiation and they dug wells all over the facility, and they would have monitors monitoring what type of radiation, how much radiation and knew how fast radiation could transport in the environment.”

Great care went into studying radiation in the Etowah River including the construction of rafts to track and map the flow of radiation as well as the atmospheric effects of radiation.

“This was all unknown,” Mahaffey said. “You have to build a facility that’ll test it in real ways, not just computer simulations and it has to be somewhere where you’re not potentially going to wipe out a city.”

When the GNAL closed, Mahaffey said he believes the facility was able to accomplish everything it was asked to accomplish.

For Mahaffey, what happened inside Dawson Forest was an important piece of atomic history that he doesn’t want to be forgotten.

“Do not forget history. Do not forget this history. It’s important. It’s a look into the Cold War when the Cold War was running very hot, and you have to realize the danger of it and what we were doing about it. It’s definitely not something to be forgotten,” Mahaffey said. “It was so exciting and it was the Cold War and these were warriors doing a strange war where the two warring powers were not exchanging metal. They’re not shooting each other, but it was still a war. And we won.”